NOTE: This story originally appeared in the December 2009 issue of Cascade Golfer, the Puget Sound region’s most widely-distributed golf magazine, and is reprinted here with permission. To learn how to subscribe to Cascade Golfer, visit CascadeGolfer.com.

By Bob Sherwin

As a youngster in Seattle in the golden age of flight, Karsten Solheim marveled at Charles Lindbergh’s courage and Amelia Earhart’s audaciousness. It was a captivating time for America’s youth, and Solheim — son of an immigrant family from Bergen, Norway — was romanced by it. One day, he told everyone, he would be an aeronautical engineer.

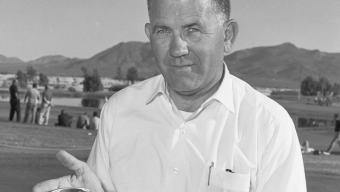

He was part right. Despite becoming intricately involved in jet propulsion and flight telemetry, Karsten Solheim (pictured in 1967 holding his Anser putter) would make his name not as the designer of the next generation of flying machines, but rather as the developer of a much simpler, yet no less ingeniously designed piece of equipment a putter.

The year 2009 marked the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Karsten Manufacturing Corp. — a company better known by the sound made by its most famous product – PING. The original PING putter, designed and developed in Solheim’s backyard workshop in the late 1950s, became the gold standard for golf-club design and has been replicated in part by nearly every putter made since.

That’s the part most golfers do know — what many do not know is that Solheim’s career, his company and his legacy all had their roots in a tiny little fishing community just north of downtown Seattle. The PING story all started in Ballard.

Grounded in Seattle

It was in 1913 when Solheim, then 2-years old, moved with his family from their home in Norway to Seattle, finding familiarity and comfort among Ballard’s large Norwegian community. Tragedy struck the family less than a year later when Solheim’s mother, Rogna, died in childbirth, leaving his father, Herman, to raise four children — two boys and two girls. The five Solheims lived on the south side of the 15th Ave. Bridge, the children commuting across the bridge each morning to attend Ballard High School.

Just as his father had once taught him, Herman educated his sons in the business of shoe repair. Even as a small lad, Karsten proved good with his hands — fixing shoes, yes, but also building cabinets and repairing cars, kitchen appliances or electrical equipment. Eventually, he became proficient enough to open his own shop, just across the street from his father’s.

Solheim understood, though, that shoe repair was not his ultimate career path. He wanted the world — in particular, the sky. Yet by the mid-1930s, at the age of 24, his life was grounded, centered around shoes. He had been forced to drop out of the University Washington before his sophomore year, because he simply couldn’t afford it (he would ultimately earn his mechanical engineering degree through a correspondence course). He wanted to engineer products that would soar through the sky — instead, he engineered those that plod along the earth

Third date – A proposal

![FirstPingIron[1]](https://www.golferswest.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/FirstPingIron1-189x300.jpg) One night in December 1935, Solheim closed up the shop and headed to a Christmas concert at Bethel Temple Church in Seattle. It was there that a 17-year-old girl named Louise Crozier, from nearby south Seattle suburb of Renton, first noticed the handsome Norwegian.

One night in December 1935, Solheim closed up the shop and headed to a Christmas concert at Bethel Temple Church in Seattle. It was there that a 17-year-old girl named Louise Crozier, from nearby south Seattle suburb of Renton, first noticed the handsome Norwegian.

“Everyone was seated, [and] I was too embarrassed to walk across the platform so I sat in the top loft. That’s when I saw him and thought, ‘My, what beautiful curly hair he has,”’ says Louise.

“After the program I asked my friend, ‘Who was that man?’ ” she continues. “She said, ‘That’s Karsten.’ And I said, ‘What’s his first name?’ Then he walked up to me and said, ‘Do you like fudge?’ He didn’t introduce himself or anything.”

The next day, the two were selected to be part of a Christmas play at the church. She was the innkeeper’s wife and he was a shepherd. He was infatuated, pumping her with question after question.

The third time they met, he proposed.

“He was 24 at the time and I was 17. I planned to attend the University of Washington; I had no thoughts of marriage,” she says. “I kind of stammered around. He told me he was very serious. Finally, I said, ‘I believe it’s the Lord’s will.’ And he said, ‘I wouldn’t have asked you if I hadn’t thought that, too.”’

In deference to the wishes of Louise’s father, a ninth-grade teacher in the Renton school system, the couple waited six months until Louise turned 18, ultimately marrying on June 20, 1936.

It wasn’t a good time to be taking on extra expenses. The United States was deep into the Great Depression, and Solheim now found himself tasked with providing for a family. Neither one could continue their education at UW. Solheim supported his family at his downtown Seattle shoe shop, while Louise stayed home, caring for the first three of their four children.

Early in 1940, Solheim sprained his wrist and was forced to take a break from repairing shoes. The forced downtime allowed him to recapture his lofty dreams, and he began to look actively for a new career. He thought about selling cars, but with the buildup to the War, there were continuing shortages.

He finally took a job as a travelling cookware salesman — anything to break out of the socio-economic rut in which his family seemed destined to remain.

“That first year we about starved,” says Louise, 91 at this time and living in Phoenix. “Then the next year, he was the top salesman on the West Coast. He loved people and his goal was to do better.”

The PING moment

Over the next 20 years, Louise remembers, the Solheims would relocate 21 times, travelling all over the country. When war broke out, Solheim took a job in the shipyards in San Diego, in the development of the military fleet. That turned into a job developing the Fireball jet fighter, then another as engineer for the Atlas missile’s first ground guidance system. In Ithaca, N.Y., Karsten developed a radar guidance system for General Electric; in Syracuse, he helped perfect the rabbit-ear antenna for the first television sets.

It was after leaving Ithaca that the second great marriage of Solheim’s life would occur — that between a man and his golf club. After building a house with Louise in Redwood City, Calif., in 1956, he began to play the game with increasing frequency — and an increasing frustration all too familiar to golfers everywhere.

By day, Solheim worked on behalf of GE, Bank of America and Stanford University to develop one of the world’s first computer systems. By night, he labored in the couple’s garage on a putter that would help him shave strokes from his golf game.

One of these two products would ultimately bring him lasting fame and fortune.

“I thought it was a nice distraction, an interesting hobby,” Louise says of Karsten’s late-night garage sessions. “I remember him saying, ‘It’s not my fault the ball doesn’t go in hole. [The putter’s] not made right. The weight needs to be in the heel and toe.”’

Solheim used a hot plate to bend the metal, and an auto body file to form the clubs. His design focused on shifting the weight to the outside edges of the club, called “perimeter weighting.” Also, instead of placing the hosel at the heel of the putter, he moved it toward the center, creating a wider cavity-back and sweet spot, and a firmer, more controlled stroke.

“We had a two-floor apartment then and the kitchen was on top,” Louise says. “I remember him running upstairs. He was so excited. He said, ‘I got a name for the putter!’ He put the ball on the floor and hit it. ‘PING!’”

“I said, ‘That’s nice, honey, dinner’s ready.’ I’ve felt so bad ever since because he was so excited. That moment changed our lives.”

‘Double Ugly’

The moment in their kitchen may have represented a literal “stroke” of genius, but Solheim’s design was slow to catch on. To help jump-start sales, Solheim reverted back to his travelling salesman days. Whenever there was a West Coast golf event, the congenial Karsten, with his distinctive Colonel Sanders-like chin beard, would simply lay his putters down alongside the practice green. It wasn’t long before the professionals — including Julius Boros, Gary Player and Jack Nicklaus — began to see the benefits.

“I was working for Columbia Edgewater [in Portland] and we hosted the 1961 Portland Open,” says Bunny Mason, a longtime golf teacher and course designer whose credits include Big Meadow at Black Butte Ranch, and who is considered by many the person most responsible for turning Central Oregon into the resort golf destination it is today. “Karsten comes in with all these very rough-looking putters. He introduces himself and I thought, ‘Here’s just another guy with a dream.”’

Solheim told Mason that any pro who wanted one could have it, and that Mason could keep any left over. The putters quickly became scarce, but Mason still wasn’t completely sold. The next year, Solheim mailed Mason 100 putters to sell at a local golf show.

“They were revolutionary but double-ugly,” Mason says. “I said if they sold, I would eat the box they came in. Well, I was never so wrong in my life. Everybody eventually copied it or took the principles of its design.

“But it was still ugly.”

Mason says that what impressed him most about Solheim was that “he was a no-B.S. guy. He was a scientist — honest, straightforward. No one could say an unkind word about him. Just a regular guy. A great innovator. He really left a big footprint in the business.”

By 1966, Solheim had designed an even better putter. It was Louise who suggested the name; she called it the “Answer.” Karsten didn’t like it, and said it was too long to be inscribed on the toe. To which Louise replied, “Fine, Anser.”

It fit. The Anser, as it was known, became the most popular putter in the world. Sales soared after Boros, one of the first pros to pick up Karsten’s putters off the side of the practice green, won the 1967 Phoenix Open with it.

“At one time, I was operating three golf shops,” Mason remembers, “and I could not sell anything but the PING Anser. I couldn’t give anything else away.”

Karsten left his job with GE in 1967 to devote his full efforts to his fledgling company. One of his first salesmen was Jim Bourne, the current and longtime co-owner of the North Shore Golf Course in Tacoma. He first met Karsten in 1961 in the same fashion as Mason; Karsten walked in his pro shop, and handed him his innovation.

“I ended up working for him for 37 years,” Bourne says. “He was a great guy who loved talking about golf clubs and golf balls, a guy who didn’t mind getting on the end of the plank.”

He was also a guy who loved Seattle. Despite relocating from Redwood City to Arizona to be closer to the heart of the golf business, Karsten and his wife would escape the desert heat every summer at their second home, on the west side of Bainbridge Island. Louise still spends time here in the summers.

Solheim died in 2000, but has built a legacy that will long outlive him. From one garage-built putter, PING became the No. 1 seller of irons in the 1980s. Once peddled course-to-course, practice green to practice green, PING clubs are now sold in 70 countries. Once consisting of one man putting his clubs in the hands of as many pros as he could find, PING now employs over 1,000 workers, and professional golfers have won more than 2,500 tournaments worldwide using PING equipment. In addition, the company sponsors the biennial Solheim Cup, the Ryder Cup of women’s golf.

In 2006, the University of Washington honored Solheim by inducting him into the UW mechanical engineering Hall of Fame. Louise later established a scholarship fund in his name.

“Some of our dearest friends come from that time,” Louise said. “It’s been a good life.”